LitReactor

A BookLikes home companion to LitReactor.com, an online haven for readers and writers.

BOOKSHOTS: Coincidence by JW Ironmonger

Title:

Coincidence: A Novel

Who wrote it:

J.W. Ironmonger, a British software consultant and possibly one of the only Europeans to see a wild Javan rhino.

Plot in a Box:

Thomas Post is an academic who believes all coincidence can be explained, until he meets Azalea Lewis, whose life events defy logic.

Invent a new title for this book:

The Birthday Gull

Read this if you like:

In the Woods by Tana French, or Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

Meet the book's lead(s):

Thomas Post, a gangly academic in his thirties and Azalea Lewis, a redheaded woman who was abandoned mysteriously as a child.

Said lead(s) would be portrayed in a movie by:

I don’t know why, but Tom Hanks comes to mind for Post, and maybe a younger Nicole Kidman for Azalea.

Setting: Would you want to live there?

Part of the story takes place in a village on the Isle of Man in the late seventies, which seems quaint if a little stifling.

What was your favorite sentence?

Hitsuzen is an event that happens according to some preordained plan or design. Something that was always supposed to happen.

The Verdict:

Coincidence is an intriguing novel on a conceptual level. First published in the United Kingdom as The Coincidence Authority, Ironmonger structures the plot around a series of dots that the reader must connect in order to view a full picture. Novels tend to naturally do this, of course (at least, most of them do) but in Coincidence, all patterns are worth noting. It’s the kind of book that appears to be designed to make readers think; not an easy task to pull off when done so conscientiously.

Although certain elements occasionally feel a bit forced as a result, the story itself is enjoyable enough to ignore these moments. Not to mention, Ironmonger isn’t entirely unsuccessful — it’s hard to read Coincidence and not puzzle over its themes. The story prompts a rather complex question: can the single, miniscule movement of a bird change several human lives forever?

One of the best qualities a suspense novel can possess is a sense of deepening as the pages turn, as opposed to the outcome becoming more obvious. From page one, I was interested, but by the end of the second chapter, I was absorbed. Ironmonger’s language is frank; it’s not about elaborate prose, but small details, such as how a character holds a walking stick or drums fingers on a chair. Using this technique, Coincidence forms characters that are, for the most part, well-developed and engaging, if just a little bit cliché at times (particularly the scatterbrained academic).

Overall, Coincidence deserves credit for a highly ambitious plot and a strong thread of humanism that presents itself in warm characters and a vivid portrait of Uganda in the 80s and 90s, where a portion of the plot takes place. Slightly uneven in places, Coincidence is always earnest and admittedly a bit ingenious. Ironmonger likes to step outside of the box, if the premise of his earlier novel, The Notable Brain of Maximilian Ponder is any indication. Hopefully, American publishers will be releasing more of his work in the near future.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Leah Dearborn

BOOKSHOTS: Demon Camp by Jennifer Percy

Title:

Demon Camp

Who wrote it?

Jennifer Percy is a Pushcart Prize and NEA Grant winner whose work has appeared in Harper’s and The New Republic.

Plot in a Box:

A reporter explores small communities in the South where soldiers are delivered from their haunting demons of war.

Invent a new title for this book

…And Into the Fire

Read this if you liked:

Jar Head by Anthony Swofford, Black Hawk Down by Mark Bowden, Going After Cacciato by Tim O'Brien

Meet the book’s lead:

Jennifer Percy interviews Afghanistan veteran Caleb Daniels, who believes he's fighting a spiritual war against the demons of the war in Afghanistan.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

Woody Harrelson, as grizzled as he can get.

Setting: Would you want to live there?

No. What’s incredible about this book is that while it sounds like fiction, it’s not. These people believe they are haunted by demons. They see them everywhere they go. Would you want to live there? I mean, seriously? Even if it was Tahiti? Plus, they live in a small town in the less than pretty part of Georgia (which has many pretty parts but those parts this part is not), so…

What was your favorite sentence?

Jennifer Percy is so good sometimes, she deserves a couple, so indulge me:

…from which they dropped the Special Forces recon team down the woven nylon ropes deployed on either side, letting them slip to the ground quiet as raindrops down leafstalks.

His eyeballs move beneath closed lids like things turning over in the womb.

The Verdict:

Demon Camp is […] “a place in South Georgia where the layer between heaven and earth is very thin,” and Sergeant Caleb Daniels traveled there to get rid of The Black Thing. “It’s called deliverance,” he said. “It works wonders.”’

His story is a must-read for all of us. It’s vital to our understanding that the demons of war will not, whatever the treatment, retreat. And ultimately, the book’s tag line “A Soldier’s Exorcism” is ironic (I’m not giving anything away because this isn’t that kind of book), because the main character, and anyone suffering from this kind of trauma, cannot in the end be completely exorcized.

As Percy says, “Then I knew that God was just a word he used to talk about other things [...] George W. Bush borrowed the vocabulary of religion for his war. Now Caleb borrows the vocabulary of war for his religion.” Which is the crux of the book. This is not a "war-book" in the traditional sense. Not much of the book takes place anywhere but right here on American soil, after the war, where a new war is being fought against PTSD—what these characters believe to be Demons. But Percy walks a fine line between both of these interpretations, respectful yet critical, concerning herself less with the vocabulary used to describe the trauma and more with the trauma and its manifestations. “Physical pain is corporeal and so wounds feel like evidence… If the existence of pain is always, if possible, confirmed through the flesh, then the pain of the mind—psychic pain, tragic pain, the pain of broken hearts—must also desire such confirmation.” Ultimately, this book is a moving piece of literature, moving us to acknowledge the seeming inevitability of PTSD; there's a realization that, call it Demons or call it PTSD, this thing has been haunting us and will continue to haunt us as a nation, immune to its exorcism as long as we practice faith in war.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Chris Rosales

Did you ever send notes to your High School crush?

Pamela Ribon did and kept copies of them all. Tiffany Turpin Johnson reviews a memoir of adolescent fervour for LitReactor.com

Title:

Notes to Boys (And Other Things I Shouldn't Share in Public)

Who wrote it:

Screenwriter and author Pamela Ribon, who already has several bestselling books to her name.

Plot in a box:

In a mostly funny memoir of her 1990s-era teens, Ribon recounts the hardships of being a pubescent writer with too much word vomit and no internet trash can.

Invent a new title for this book:

Wherefore Art Thou, Adolescence?

Read this if you liked:

Bossypants by Tina Fey

Meet the book's lead:

Little Pam is like any other thirteen-year-old girl...who writes two-hundred-page notes to boys. More than once.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

Eden Sher from ABC's The Middle, if she dyed her hair blonde. She's so adorkably irritating, but you know she's going places, and you wanna go along.

Setting: would you want to live there?

Um, no. Let me rephrase that. HELL no. There's racists, bullies, bigots, book-burners, and boys who don't write back. And I thought my high school was hell!

What was your favorite sentence?

Life. It's pretty much bullshit. Brought to you by the number fifteen.

The verdict:

There’s basically two main characters switching perspective throughout the memoir, although they’re ultimately the same person. Grown-up Ribon narrates us through her early ‘90s journey as Little Pam (LP), the wannabe writer who kept copies of the copious letters she sent to every teenaged boy unfortunate enough to look her way—and sometimes even to those who never did. Here and there we get sprinkles of (mostly bad) poetry and short stories. You can’t read too many chapters in one sitting, either because you feel too embarrassed at LP’s follies or too overwhelmed by flashbacks from your own adolescence. If you were ever a teenaged girl, at least.

Ribon’s a comedian at heart, so most of the book is funny, with just enough heaviness to remind you that you’re reading a memoir, not a Disney Channel script. There are some dark moments, although Ribon mostly glosses over them in favor of focusing on the more widespread embarrassments of adolescence. There were a couple places where this became an issue, because in our culture of rape and bullying, it’s no longer okay to play down the inflated feelings of angst that go along with the teen years, especially for young girls. But if you can get past the one suicide joke, in particular, she does get serious on the issue later on.

The letters are reported as-is, so there’s loads of distracting [sic]s in the way, and Ribon can’t help interjecting commentary every other sentence, leering at each of LP’s imperfections like a nitpicking mother. I remember being a teenaged girl struggling to be heard, and I just want to scream at Ribon, Let the girl speak already! But it’s just because Ribon’s made me see myself in LP, so that even while I’m annoyed by the girl I want to hug her and tell her everything will be okay, that I love Siamese Dream too, that I miss my K too, that we all find our Nice Boy one day and so will she.

So ultimately I enjoyed the book, and I rooted for LP even when I wanted to slap her. The last quarter of the book is the best, so hang around for the payoff.

BOOKSHOTS: Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol to A Clockwork Orange-- How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos

Title:

Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol to ‘A Clockwork Orange’—How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos

Who wrote it?

Robert Hofler, former senior editor at Variety, currently a theatre critic for The Wrap.

Plot in a Box:

The title pretty much says it all: Sex in mainstream media, 1968-1973.

Invent a new title for this book:

As the actual title may or may not be taken from this My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult album, for the alternate titling let’s lift the name of the first track from that record, The International Sin Set.

Read this if you liked:

Hofler’s previous book, Party Animals, Robert Evans’s The Kid Stays In The Picture, and Kirby Dick’s documentary This Film Is Not Yet Rated.

Meet the book’s lead(s):

Philip Roth, Gore Vidal, Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, John Schlesinger, Lance Loud, Jack Nicholson, Bernardo Bertolucci, Mart Crowley, Ken Russell...If you don’t know some of these names, read the book.

Said lead(s) would be portrayed in a movie by:

David Bowie played Andy Warhol brilliantly in the film Basquiat. Thomas Dekker played Lance Loud in Cinema Verite. Of all the names left on the above list, I think Jack Nicholson is the toughest. However, as you can see, Leonardo DiCaprio might be the man we’re looking for.

Setting: Would you want to live there?

I’ve always fancied living during the 60s and 70s. A resounding yes!

What was your favorite sentence?

"Never a stickler for accuracy, the newsweekly went on to complain that ‘the characters are all homosexuals and junkies,’ despite the fact that Nico had sired a child by actor Alain Delon and committed other flagrant acts of heterosexuality."

The Verdict:

Sexplosion is a bona fide page-turner. Hofler’s extensive research into a relatively short period of time bursts forth on the page like a swinging period film. Think Boogie Nights without the “bad-time” consequences in the latter half of the narrative. To be fair, Hofler does present the troubles these trailblazing authors and auteurs met, both from censors and certain sects of the populace not ready for all that taboo-breaking, but overall their efforts are presented in a positive light. Fascinating, funny, and thorough, this book is a must for anyone interested in media studies and our not-too-distant cultural past.

While Sexplosion covers all aspects of sexuality during the period, perhaps the most eye-opening narrative involves the homosexual revolution in novels, non-fiction, plays, and films. I had no idea that The New York Times was such a gay-bashing, socially conservative publication, throwing around the word “faggot” without blinking an eye. Ditto for studio executives and film crews, who were clearly uncomfortable with gay themes in the works of Schlesinger, Vidal, and a host of others. Though we still have some distance yet to travel, overall we’re doing well where cultural acceptance of homosexuality is concerned, and Sexplosion tells the story of the people who made our current enlightenment possible.

I’m honestly hard-pressed to find any flaws with this book. There aren’t many female voices explored, but Hofler addresses this in his epilogue (unfortunately, much of the mainstream media was still dominated by men at the time, even if some of them were members of a minority as well) and overall the text is decidedly not anti-feminist in nature. For example, the author sympathizes with actresses Susan George and Maria Schneider, whose misgivings about scenes of rape and sodomy were cruelly dismissed by their respective male directors and co-stars. He also dedicates significant chunks of the book to other actresses with “controversial” viewpoints on sex (Jane Fonda, Vanessa Redgrave, etc.) as well as prominent female critics like Pauline Kael. This plus his epilogue show me that while Hofler’s lens may be focused on a particular group of artists who crossed certain boundaries in mainstream media, and those particular artists all happened to be male (because sexism), the author is no less concerned with women and their experience during this culturally transformative period.

In short, Sexplosion is pretty damn good. Check it out!

BOOKSHOTS: USA Noir edited by Jonny Temple

Title:

USA Noir: Best of the Akashic Noir Series

Who wrote it:

Edited by Johnny Temple, this collection includes tales from such literary gems as Joyce Carol Oates, Michael Connelly, and Megan Abbott.

Plot in a box:

A collection of the best tales from the nearly sixty volumes of geographically-themed anthologies of American noir.

Invent a new title for this book:

Welcome to the Jungle: Concrete Noir

Read this if you liked:

Any of the other books in the Akashic series. Or if you just like your fiction short and dark.

Meet the book's lead:

There are far too many to list. One of my favorites is Ray from Karen Karbo's "The Clown and Bard" (set in Portland), who's nearly comical in his inability to accept responsibility for his wife's murder.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

Jared Leto. Because this film would have a lot of roles, and after Dallas Buyers Club, it's clear he can play anyone.

Setting: would you want to live there?

I sorta do already, being that all of the stories are set somewhere in the US. But (amazingly) there's no version yet for Atlanta (which is where I call home), and I'm grateful for that. I'm pretty sure it'd be easy to put one together, but I don't think I'd want to see that much darkness so close to where I live.

What was your favorite sentence?

"I could admit, if I let myself, there was a beauty in it, if you squinted, tilted your head. If you could squeeze out ideas of the kind of beauty you can test in your palm, fasten around your neck, never have an unease about, a slip of cashmere, one fine pearl, a beauty everyone would understand and feel safe with. But I wouldn't really do that, not for more than a second."

-from Megan Abbott's "Our Eyes Couldn't Stop Opening," set in Detroit

The verdict:

This book is not for the faint of heart, and it's not for anyone who likes to cuddle up with a cozy mystery and a hot cup of tea before bed. This collection of noir Americana, hand-picked from the already-stellar Akashic anthology series, features the work of top contemporary writers along the ranks of Lee Child and Laura Lippman, and is full of dark-hearted fare that'll haunt your dreams.

Each story hails from a different urban underbelly, but they all share a few commonalities. Setting is always a character, helping to set each story's gritty atmosphere, tone, and mood. Grisly urban details are used as a subtle form of foreshadowing between the damaged, often unlikable characters and their complicated, usually dysfunctional relationships. A lot of the main characters are unreliable or downright devious, and many harbor deep faults—desperation, irresponsibility, longing for youth—that drive every action. There's a feeling in each story of innocence lost, or of its impending loss, and the reader is helpless to stop it. Many of the stories are both romantically and sexually bleak, as the characters are incapable of experiencing anything resembling love. Issues of race and social strata divisions are prevalent.

But the stories aren't merely a series of depressing social essays on the human condition. Just when I would begin to feel like I needed to watch a Disney movie for some balance, along would come a story that surprised me. Like Julie Smith's New Orleans-set tale, which showed me noir can be a breath of fresh air, even if you fall in love with the character you feel certain will ultimately meet their doom. Or Megan Abbott's Detroit ditty, which showed me the suburbs can be just as scary as the darkest corners of the city. Or Karen Karbo's Portland story, which taught me I can root for a murderer, as long as he's got a sense of humor.

These stories will make you feel something. There's no doubt about that. It's just a matter of what. The book's already gleaning awards, and I can see why. Just don't expect a cozy read, and have a Disney flick on hand for balance.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Tiffany Turpin Johnson

1

1

BOOKSHOTS: The Bear by Claire Cameron

Title:

The Bear

Who wrote it?

Claire Cameron, a former wilderness instructor in Ontario's Algonquin Park.

Plot in a box:

Anna is five years old and soon she will be six and Anna and her brother Stick and Momma and Daddy go camping and a big black dog comes and there's a piece of meat it has on Daddy's shoe and Momma is lying in the plants the blood is on her neck and in her shirt and it is ripped and she looks like not Momma but a doll.

Invent a new title for this book:

33 Chapters and an Epilogue on Why You Should Never Take Your Kids Camping

Read this if you like:

I don't know, crying? Horror stories about camping trips gone terribly wrong? Into the Wild?

Meet the books leads:

Anna and her brother she calls him Stick he is two years old and almost three and he bugs her lots of times because she is five years old and soon she will be six and Gwen teddy bear she is brown.

Said leads would be portrayed in a movie by:

Dakota Fanning, but like I Am Sam Dakota Fanning, not Twilight Dakota Fanning, or maybe Drew Barrymore circa E.T. (Anna); Nicky and/or Alex from Full House (Stick); Creasy Bear from Man on Fire already has a working relationship with Dakota, while the teddy from Firestarter could be called in to work with Drew (Gwen).

Setting: Would you want to live here?

Me? Absolutely not. It a) takes place in Canada and b) involves camping. This book has put me off camping (and possibly Canada) for life.

What was your favorite sentence?

"I sing a song and walk and da da da down by the bay, where the watermelons grow and I wish I had a big piece of watermelon and I look and there is a lake and no watermelon."

The Verdict:

Good gracious, this book is absolutely heartbreaking. At first I couldn't read more than a chapter at a time, but I needed to know what happened, so I read most of the book in these short bursts of emotion that were tremendously powerful for such a small book. It's only about 220 pages, but I'm pretty sure if anyone read the entire thing straight through, that person would just...die. His or her heart would simply burst. It's too much. This book floored me. I don't want anyone to have to suffer the pain I experienced reading The Bear, but at the same time I want everyone on the planet to read this book and feel these horribly complex and yet intensely primal emotions.

"I look around and it's mess mess mess."

For the great majority of the book, a five-year-old girl is wandering around in the wilderness trying to protect her two-year-old brother. That's hard enough to deal with, but she's also the narrator, which means that you're in her head and feeling exactly what she's feeling. You're right there with her as she's trying to figure out why her parents haven't come by to make her lunch or take her home or tuck her into bed or any of the things that parents are supposed to do for their children.

"The sun gives too much shine and there are trees everywhere with their dark in between and I don't see anything I know."

Obviously it deals with a very specific incident, a bear attack, but really this is one of the most universal stories I've ever come across. The gravity of this girl's loss, the immensity of her frustration and confusion, and the sheer power of her resolve and determination not to let her parents down through taking care of her brother is beyond anything I ever expected when I picked this book up and started reading.

"It is raining hard and there is water all over me and I am shaking and so so cold and I think I will probably get dead."

It's difficult for me to even write this, because it means I have to remember the book, and think about how difficult it is emotionally, and how bluntly the concepts of trauma and loss and abandonment are confronted. It doesn't matter, though, because it's not like I've been able to think about anything else since I put it down. I even started looking into the history of fatal bear attacks in North America, which was probably a terrible idea if I ever plan to go into any forested area ever again.

"I put my head back down and I won't ever sleep a long time maybe forever."

Who am I kidding? I am never going into any forested area ever again. Watch out for bears, folks, and read this book.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Brian McGackin

1

1

BOOKSHOTS: 'The Corpse Exhibition' by Hassan Blasim

Title:

The Corpse Exhibition: And Other Stories of Iraq

Who wrote it:

Hassan Blasim, author of The Madman of Freedom Square (longlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize of 2010) among other titles.

Plot in a Box:

The Corpse Exhibition is a collection of dark, fablelike stories from some of Iraq's blackest days.

Invent a new title for this book:

The Art of Killing Softly

Read this if you like:

The Septembers of Shiraz by Dalia Sofer or Cairo by Willow Wilson.

Meet the book's lead:

The protagonists of The Corpse Exhibition are an eclectic lot, from book-loving assassins to a fake Mexican going by the conspicuous pseudonym of 'Carlos Fuentes.'

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

Despite being written by a film director, I have a difficult time envisioning The Corpse Exhibition as a movie.

Setting: Would you want to live here?

Not if you paid me.

What was your favorite sentence?

For God's sake, what's the point, as we are about to embark on war in poetry, of someone saying, "I felt that the artillery bombardment was as hard as rain, but we were not afraid"? I would cross that out and rewrite it: "I felt that the artillery fire was like a carnival of stars, as we staggered like lovers across the soil of the homeland."

The Verdict:

The Corpse Exhibition is not an easy book to categorize or review. Where to even begin? Blasim presents a brutal side of humanity. Book shot is appropriate here; these short stories are like swigs of whiskey to be downed in quick succession. Men have their skin sliced off, women are whipped and forced into prostitution. Much of the pain is senseless, such as the occasion when one character mutilates a vegetable seller’s face because he was “drunk and felt like it.” Through this prism, the reader gets a rare glimpse of a broken, lawless land.

The author writes primarily in Arabic, so the February debut is actually a translation, with many of the stories having already been banned across the Middle East. Blasim’s language is visceral, gritty, and completely unflinching on even the most graphic of topics. There are traces of magical elements woven in, including a precognitive compass, a dead man who speaks to the audience in monologue, and a society of highly sadistic assassins. Some of the stories read like Gothic fables, reminiscent of the violent and confounding original tales of the Brothers Grimm or Arabian Nights. It bears mentioning that in this book, dull conclusions are anathema. Every story ends with a bang (sometimes in the form of a literal explosion).

The author’s own background is as worthy of note as many of the tales in The Corpse Exhibition. Blasim was forced to flee Iraq for Finland to avoid persecution by the Hussein dictatorship after making a controversial documentary. One can’t help but wonder whether some of the themes in the book might be slightly self-referential. In a story called ‘An Army Newspaper,’ Blasim analyzes even those who write about war instead of waging it, sarcastically calling slaughter the inspiration of “such artistic largesse, such love, such poetry.”

The Corpse Exhibition is a truly unique collection of work, guaranteed to satiate anyone with a thirst for the surreal, macabre, or even those interested in seeing the conflict in Iraq from a new perspective. It's not a pleasant read, but the value of the stories is undeniable, and there isn't a single bit of fluff in the entire collection. Skip the bedtime tea and cocoa when reading this book and break out something harder—you’re going to need it.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Leah Dearborn

BOOKSHOTS: 'This Dark Road to Mercy' by Wiley Cash

Title:

This Dark Road to Mercy

Who Wrote It?

Wiley Cash, author of New York Times bestseller A Land More Kind Than Home.

Plot in a Box:

Two young sisters are "rescued" from foster care by their deadbeat ex-ballplayer junkie dad and taken on a cross-country road trip to see McGuire and Sosa's epic battle to become baseball legends, but they are followed by men their father would rather avoid, probably because of the big duffel bag full of money he nervously totes around but never wants to talk about.

Invent a New Title For This Book:

One Last At Bat

Read This If You Like:

To Kill a Mockingbird, or if you wish Judy Blume had written Southern crime fiction.

Meet the Book's Lead:

Easter, the oldest of the girls, determined to protect her little sister from their worse than useless father. Although she is resolute in her disdain for the man, she still can't help wanting to get to know him better.

Said Lead Would be Portrayed in a Movie By:

Chloe Grace Moretz a few years ago, a young actress who excels at playing precocious kids who are smarter than their adult tormentors.

Setting: Would You Want To Live There?

Easter and her little sister Ruby see the country between North Carolina and Missouri through the windows of car and countless crappy motels, all while being pursued by both the law and a murderous madman. It's not an ideal summer vacation.

What Was Your Favorite Sentence?

So that's what me and Ruby started calling ourselves; I was Boston Terrier and she was Purple Journey. Boston Terrier: I'll admit it sounds silly when you first hear it, but if you split it up into a first name and a last name I think it sounds kind of pretty—fancy and a little bit dangerous, like the name of a woman in an action movie the hero can't quite trust but falls in love with anyway.

The Verdict:

The plot is a lot like No Country For Old Men, if Llewelyn Moss had been accompanied by his two young daughters as he fled cartel hitmen and the law, all the while trying to keep the girls convinced it was all just a fun family road trip with Dad. The story is mostly told by Easter Quillby, the oldest girl, who is easily the stand-out character of the book. Her sections are the most enjoyable parts of the story, so much so that you will start to find yourself becoming irritated when the narrative shifts to the other two POVs: the girls’ government appointed guardian and the vengeful hitman chasing their father. They are both perfectly functional, serviceable support characters for a crime caper, but neither manages to be more than a distraction filling pages between Easter's chapters. Her voice is the most interesting, her perspective the most unique, and her story the most compelling. When Easter speaks, This Dark Road To Mercy is something truly exceptional. Her chapters read like a Joe Lansdale mystery told by a teenage girl. Easter is smart enough to know when the adults are lying to her, but not yet old enough to do anything about it. It’s rare for a crime drama to make its most helpless character the primary point of view—even Chandler’s most luckless private eye can still go down shooting—but this intriguing twist on perspective is undercut every time the camera shifts back to one of the grown-ups. In these chapters the reader is drip-fed a bunch of information and backstory through the more easily digestible adult perspectives. That’s not to say they are in any way poorly written, it’s just that the adults’ chapters ruin all the fun of trying to puzzle out the mystery with Easter’s limited resources and access to information. That being said, Easter’s short time in the spotlight makes This Dark Road To Mercy a worthwhile read.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by BH Shepherd

BOOKSHOTS: ' Andrew's Brain' by EL Doctorow

Title:

Andrew's Brain

Who wrote it?

E.L. Doctorow, the man behind such novels as Ragtime, Billy Bathgate, and The March.

Plot in a box:

The title isn't misleading. Andrew's Brain is told entirely in conversation, from the perspective of the titular character as he relates stories, memories, images, thoughts and ideas from his life to what I assume is a psychologist of some sort, known only as Doc.

Invent a new title for this book:

The Art of Unconstrained Emotions

Read this if you liked:

Edgar Allan Poe, Albert Camus, psychology, neuroscience, little people, scratching your head and wondering if anything around you is actually real.

Meet the book’s lead:

Andrew, a self-deprecating cognitive scientist with a penchant for young women, cynicism, and talking in the third person.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

Leo, The Great, in an Oscar-winning turn.

Setting: Would you want to live here?

In a shrink's office? In someone else's head? In prison? In a computer? Hmm. Yeah, sure, why not.

What was your favorite sentence?

"And just now, loud as a clap of thunder, a poor dumb gull riding the winds has bashed his head against the windowpane. I exchange looks with his glazed eye as he slides a smeared red funnel down the snow on my window."

The Verdict:

Yes, this is not the E.L. Doctorow you know. Don't bug out, though, okay? I mean, the dude is 83 and has won or been nominated for every major fiction award since his career began in 1960. Let's cut him some slack, yeah?

Really, you should. Because Andrew's Brain is — oh, I'm trying not to overreact here, believe me, but... — in fifty years, this may be one of those kinda-sorta career-defining novels.

I know, I know. Ragtime! Billy Bathgate! The March! Dude's got chops. Dude's got a shelf full of BOSS. But the great thing about what Doctorow's done before is that he can take chances now. Andrew's Brain is most definitely a chance. I'm glad he took it.

This Andrew, this guy with the brain, he's such a bitch, honestly. Guy blames himself for every damn thing that's gone wrong in his life, in the lives of those around him, hell, in the world at large, it seems. I'm probably exaggerating — am exaggerating, but only slightly — but this guy is depression personified. Not the kind of depression that leads to suicide; the kind of depression that leads to being a cynical asshole who has serious issues with the way humanity has evolved into a big, steaming pile of what-the-fuck.

Andrew has excuses, though. He's had a life full of bad experiences. He suffered through the death of his first child (totally his fault), the demise of his marriage (kind of his fault), and the death of a lover half his age who also birthed his second child, who he then leaves with his ex because he fears he can't be an adequate father. After all this, he finds himself teaching high school and then working in the White House before winding up detained somewhere undergoing psychological treatment.

Follow?

OK, cool, because now you should know that Andrew is completely unreliable. UNRE-FUCKING-LIABLE. Up front, you learn he calls himself Andrew the Pretender. And he says things like "Pretending is the brain's work" and "I can't trust anyone these days, least of all myself." And then you can't help but wonder if what Andrew says, what he sees, or what he's experienced is even real at all.

But you'll be OK with that. I was, because, really, I deal with that every day. And so do you. We're all unreliable narrators, and so is everyone around us.

Either way, Andrew's Brain, on top of being another of those head-scratching mindfucks — why do I keep signing up for these? — is funny, playful, thought-provoking, disturbing, sly, and just plain different. The fact that this came from Doctorow's brain still blows mine. It's a worthy entry into his catalogue, even if you're left at your leisure to put the pieces together.

That's what brains are for though, right?

Bookshots review written for LitReactor by Ryan Peverly

2

2

BOOKSHOTS: 'What We've Lost is Nothing'

Title:

What We’ve Lost Is Nothing

Who wrote it?

Rachel Louise Snyder, previously known for nonfiction works and contributions to several radio programs. More info about Snyder here.

Plot in a Box:

The citizens of one suburban street re-examine their lives in the wake of a mass burglary. Emotional drama ensues.

Invent a new title for this book:

We Were Dead Before The Ship Even Sank (Okay, I didn’t invent this title, but it works.)

Read this if you liked:

Any socio/psychological Lit Fic, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, and Crash (not the celebrated J.G. Ballard novel or David Cronenberg's superb film adaptation; the other one).

Meet the book’s lead:

Mary Elizabeth McPherson, who happens to be at home during the burglaries. She becomes a darling to the media and her classmates.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

Let’s go with Jennifer Lawrence, but really, you could choose any young, talented, popular actress right now.

Setting: Would you want to live there?

I lived in Chicago for about three and a half years, and though I still love that city, I realized long ago it wasn’t my home. So as this book is set in Oak Park, a suburb of Chi-town, I’d probably have to say no. Plus, Snyder doesn’t exactly paint the town and Ilios Lane, the burgled street, as particularly idyllic. Double no!

What was your favorite sentence?

"He was like a city under siege, full of broken buildings, and yet, inexplicably, light still flickered from some unknown source."

The Verdict:

I see Snyder as an author with significant potential. WWLIN is her debut novel, and while overall the writing is quite good, the story suffers from a greater desire to make a point, and an inability to really make it. This isn’t a bad book, necessarily, just an unfocused one. We explore the impact this burglary has on an entire street, and we see the positive and negative effects felt by each household. The problem is, while the characters are all fleshed-out well enough, I feel Snyder only scratches the surface—in other words, she’s interested in the socio/psychological ramifications of a life-altering event, but she doesn’t really go there. She occasionally digs deeper for certain scenes, but overall the inner thoughts and outer reactions of the characters are about what you’d expect, given the circumstances. Plus, given the shear volume of characters, there’s not a lot of variety in these thoughts and reactions.

Furthermore, Snyder tends to meander, and no one character was compelling enough to really captivate my interest. I found Susan and Michael McPherson, parents to the aforementioned Mary Elizabeth, a tad off-putting, particularly Michael, who lapses so quickly and gruffly into racist suspicions of his Cambodian neighbors, he’s almost instantly unlikable, and the psychological motivations behind his illogical thinking aren’t solid enough to elicit any real empathy for him. The most interesting character is Mary Elizabeth, but her journey has nothing to do with race relations, and everything to do with sexism and the downright bizarre expectations placed on young girls in this country. Compelling stuff, absolutely, and Snyder handles it well, but the question must be asked: to what end?

This is why I feel the book is unfocused. At times Snyder’s “point” about racism is so blunt she’s practically beating you over the head with it, as though it were a hammer, leading one to believe What We’ve Lost Is Nothing is indeed all about racism. And yet, there’s all this stuff about inner character turmoil, identity and sexism that have nothing to do with race, straying so far into unrelated waters, we fear we might drown. If the story’s about race, why focus on all this other information? If the story’s just about people, why shine such a stark light on the issue of race?

As I said, though, at the end of the day, I didn’t hate this book. It is well-written, and Mary Elizabeth’s story is quite impressive, shedding light on just how hard it is to be a teenage girl in America. This narrative is worthwhile, but WWLIN on the whole misses the mark. I am interested to see what Snyder produces in the years to come, though.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor by Chris Shultz

1

1

BOOKSHOTS: 'Dust' by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

Title:

Dust

Who wrote it:

Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Kenyan screenwriter and winner of the Caine Prize for African writing.

Plot in a Box:

A young woman named Ajany returns to her homeland in Kenya to investigate the circumstances surrounding her brother's murder.

Invent a new title for this book:

Maybe Desert Ghost. I have to say, just about anything would be more intriguing than Dust.

Read this if you like:

Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight by Alexandra Fuller

Meet the book's lead:

Dust is less about a single person than a group of interconnected individuals, but the focus falls mainly on Ajany Oganda.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

For Ajany, I would choose Lupita Nyong’o of 12 Years a Slave.

Setting: Would you want to live here?

The violent political climate prompts me to say no, however, parts of Owuor’s Kenya are still starkly beautiful.

What was your favorite sentence?

"In the contours of old pasts, she retrieves an image: Ajany and Odidi sitting on a rock, spying on the sun's descent. She is leaning against Odidi's broad shoulder, pretending she could read the world as he did. She stammered, 'Where's it going?' He said, 'To hell.'"

The Verdict:

Dust is a novel of conflict; both in the narrative and in the prose itself. Sometimes lucid and piercing, sometimes merely chaotic, Owuor sketches a country in the midst of great turbulence with writing that is lush but choppy. Intriguing visuals are combined with a jarring sense of perspective, occasionally making it difficult to disentangle what is happening from scene to scene.

For example, there are a lot of moments like this: “Nyipir turns from the window. He is flying home with his children. Yet he is alone. Memories are solitary ghosts: Down-country.”

Along this vein, Dust has a poetic, indirect structure that can be simultaneously appealing and frustrating. Characters bounce in and out with little to no introduction, and the plot never truly coheres into a solid form. One minute Odidi and Ajany are in school, the next, they’re off married and living in Brazil, respectively. Why? Whether it’s by the author’s design or not, never expect absolute transparency here. Odidi’s demise is particularly difficult to follow; he straddles death and life for almost a chapter, never quite identifying his killer or their motivation.

The story is less driven by individual growth than it is by the character of an entire country. Owuor’s lyrical observations on Kenyan life— from passing details on the landscape, to complex political issues—are some of the most memorable moments of Dust. The coffee and pineapple plantations, ibises and machine gun chatter; Owuor’s Kenya is a potent mixture of natural beauty and the kind of extreme ugliness that only follows war. Folklore and superstition are mingled throughout the story, adding yet another layer of cultural intricacies to an already irascible and convoluted equation.

Dust is not a perfect novel, but it is a powerful one. While those in search of a tightly woven page-turner would do better to look elsewhere, a strong cultural backbone and passionate voice make Owuor’s novel of death and family in Africa a thought-provoking read, at the very least.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor by Naturi Thomas

Will #readwomen2104 change your reading habits?

Joanna Walsh blogs about her #readwomen2014 twitter campaign. The challenge is to *only* read books by women this year.

With my job, that's not practical for me, but I'm curious about whether anyone else here is going to join this challenge.

BOOKSHOTS: 'Forgiving the Angel' by Jay Cantor

Title:

Forgiving the Angel: Four Stories for Franz Kafka

Who wrote it?

Jay Cantor, award-winning novelist who also wrote The Death of Che Guevara

Plot in a Box:

Four fictionalized accounts of real-life people who loved Kafka, loathed Kafka, or struggled to escape the shadow of his legacy.

Invent a new title for this book:

Wrestling with Kafka

Read this if you liked:

Kafka’s Last Love: The Mystery of Dora Diamant by Kathi Diamant, The Complete Stories of Franz Kafka, The Stranger by Albert Camus

Meet the book’s lead:

Dora Diamant, Kafka’s last lover, carries her adoration of him throughout her life, the war and marriage to another man.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

Monica Bellucci, not in the least because she appeared in The Matrix Reloaded. Do you think Kafka would have been a fan of that trilogy?

Setting:

While I wouldn't have wanted to live in Europe under Stalin and Hitler (who would?), the labyrinthine and surreal mind of Kafka definitely would be a nice place to spend some time. Some.

What was your favorite sentence?

"It occurs to me that I’m not like other people, though I pretend to be. Of course, that I can pretend shows that I am very much like other people, for that is no doubt what they are doing too."

The Verdict:

According to Forgiving the Angel, Kafka, one of the most influential writers of the 20th century, thought of himself as only “a nearly nameless sailor, who…had simply held to his desk all night. His only skill…was to cling to the wood with sufficient desperation.” Likewise, the main characters in Cantor’s four, loosely connected stories either cling to Kafka’s legacy or struggle to escape its chokehold on their lives.

In the title story, Max Brod, Kafka’s lifelong friend, discovers a terrible betrayal against him within Kafka’s dying wish. "A Lost Story" follows an academic who discovers an unpublished parable of Kafka’s—or is the academic a part of the story himself? In "Lusk and Marianne", a militant communist falls for and marries Dora Diamant, only to discover that she’ll never love him the way she does her late, famous love. Proof? She names the daughter she has with Lusk "Franziska". Finally,"Milena Jasinska and The World the Camps Made" introduces us to another of Kafka’s lovers as she finds passion and hope in a notorious concentration camp for women.

Discussing a book like this is tricky as all short stories, even the ones by Kafka himself, are not created equal. The title story paints a gripping portrait of friendship and the dark side of an artist many thought of as an “angel”. "A Lost Story", however, read to me more like a writing exercise lacking in urgency and need. In "Lusk and Marianne", the former’s fight to reclaim his daughter from Kafka’s ghost is matched in poignancy by his blind loyalty to the Communist Party that imprisons him as their enemy. Meanwhile, in "Milena…" the love story between the two female prisoners is touching, however the connection to Kafka seems a bit forced, his presence superfluous.

That being said, Forgiving the AngeI is on the whole a moving and innovative read. It will be enjoyed by devotees of Kafka’s work, as well as those interested in giving it a closer look.

Speaking of which, to the uninitiated, which work of Kafka’s would you recommend they read first?

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Naturi Thomas

BOOKSHOTS: 'The Poisoned Island' by Lloyd Shepherd

Title:

The Poisoned Island

Who wrote it?

British writer Lloyd Shepherd, author of The English Monster.

Plot in a box:

In the late 1700s, a British sailor does something terrible to a princess on the faraway island of Otaheite (Tahiti). Now it's 1812, and sailors return from a newer trip to the island with a couple of secret stowaways: a half-breed missionary on a hunt to find his real dad, and a special tea that just may be killing anyone who drinks it. When murders begin to pile up, a River Constable risks everything—including the woman he loves—to solve the crimes.

Part history (half the characters are based on real people), part fiction, it's a well-mannered romp through time and addiction.

Invent a new title for this book:

Evil Tea and the Sailors who Loved It

Read this if you liked:

Any brand of historical fiction. The mash-up of the real with the imagined in this story is quite potent...just like the tea.

Meet the book's lead(s):

This is a hard one. There are so many to choose from! Island is something of an ensemble piece, and many of the characters carry a similar importance to the plot. So I'll go ahead and choose Charles Horton, a Constable of the River Police, who are a group of men trained to watch the Thames as ships come in and out. A gentle giant is Horton, and a smart one, introducing newfangled concepts like "motive" and "evidence" into the investigation of a seeming serial killer.

Said lead(s) would be played in a movie by:

I hate myself for this, but I sort of see Russell Crowe in this role. Mainly because I still see him as Javier in Les Miserables.

Setting: Would you want to live there?

London of the early 1800s was filthy. It was crude. And it was dangerous.

I'd like to visit.

What was your favorite sentence?

"He sometimes feels vaguely and irritatingly angered by Horton's ability to ask the single question which exposes all the hiding places in which information might be concealed."

(Mainly because there's a certain someone who always does this to me...and it drives me insane.)

The Verdict:

The Poisoned Island is immersive and addictive. The world is so vivid and well-built, it is hard to put down. And since the story is a murder-mystery, with layers of history and fact woven together with a healthy dose of magical realism, there's suspense, too, to keep you invested.

The writing is spectacular. The words drip with charm and grace. I loved letting the language carry me away, even in its crudest moments, with the roughest rabble-scrabble of 19th century London. There's no denying that this is a well-written book, with an engaging tale to tell.

But I take issue with The Poisoned Island on two levels. In the first place, there were so many characters, introduced in such close succession at the very beginning of the story, each with such similar names, I needed to write myself a cast list to keep them all straight. This is a minor complaint, to be sure, especially knowing the characters were often pulled from reality, but still. The beginning was quite confusing, what with Horton, Harriot, Hopkins, Banks and Brown all showing up in the first few pages. I felt like I'd taken a wrong turn into Dr. Seuss-ville for a moment or three.

My second issue is the bigger one, and it is this: women are almost entirely absent from the story, which would probably be less offensive if the few women included weren't flat, one-dimensional caricatures. There's the island princess, raped in the book's opening scene, who disappears and comes back as a devious spirit, the quintessential vengeful bitch archetype. There's Abigail Horton, held up on a pedestal by her husband as the very picture of perfection. And the thing is: she is perfect. Smart, gentle, content to keep herself company with her books while her husband spends days and nights away from home. She's a working man's wet dream, and she's so unrealistic it hurts. And then there's Mrs. Hopkins, the sea captain's wife, loyal and dutiful to the end, even when...well, I can't tell you that because it would be a spoiler. But none of the three women mentioned in the book were at all believable, so pigeon-holed were they. Even though London of old was apparently a man's world, women did exist, and I doubt they were all so...fake.

So while I did often enjoy this book, in the end I'm conflicted. Can I recommend a book that seems to devalue my entire gender? Am I being oversensitive? I'm not sure of the answer to either question, so I'll close it with one for you: what are your thoughts? Have you read the story, and if so, am I being unfair? I'd love to know what you think!

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Leah Rhyne

BOOKSHOTS: 'Hollow City' by Ransom Riggs

Title:

Hollow City

Who wrote it?

Ransom Riggs, author of the NY Times bestselling YA fantasy, Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children, which is also this book's prequel.

Plot in a Box:

After escaping their time-controlled "loop" with their injured leader, Miss Peregrine, Jacob, Emma and the cast of peculiar children (think X-men, only not) must scour the streets of London to find someone to help them. Only problem? The year is 1940 and London's in the midst of the Blitz, and there happen to be hundreds of evil creatures chasing them through the bombed out highways and alleys.

Invent a new title for this book:

Bird Race

Please don't ask me why. I just like it.

Read this if you liked:

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children, because you need to find out what happens.

A Wrinkle in Time, because you like YA adventure books that are written as well as most adult novels.

Meet the book's lead:

Jacob is a spoiled, troubled rich boy living in Florida, until he flies away to Wales, chasing the stories of his grandfather's childhood. There, he learns he has special (peculiar) talents, and in Hollow City he must put those talents to work to save the woman to whom his life is indebted. Sad, scared, and angry by turn, he's also madly in love with Emma, who adds a bit of spark to his life.

(That last bit is only funny if you've actually read the books. So go read them...NOW!)

Said lead would be portrayed by:

Who's young and cute and not annoying? Oh! Thomas Brodie-Sangster, AKA the boy from Love, Actually, and now Jojen Reed in Game of Thrones. He's perfect.

Setting (would you want to live there?):

London during the Blitz? I'm a total history nerd, especially over anything involving World War II, but living there? Having to send my child away to the country to avoid the bombs? No, I probably don't want to live there. But I'd love to visit!

Favorite sentence:

"Then I actually experienced my peculiar ability coming to life. Very quickly, the churning pain in my belly contracted and focused into a single point of pain; and then, in a way I can't fully explain, it became directional, lengthening from a point into a line, from one dimension into two. The line, like a compass needle, pointed diagonally at that faltering spot a hundred yards below and to the left on the mountainside, the waves and shimmers of which began to gather and coalesce into solid black mass, a humanoid thing made from tentacles and shadow, clinging to the rocks."

The Verdict:

I came into Hollow City with high expectations. Very high expectations. So high, in fact, I didn't think it would even come close to meeting them, and, in a way, I dreaded writing this review. Because you see, though I don't read much YA lit, I loved Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children. I loved the story, and the way Riggs blended these old, found photos into one cohesive album, illustrating a fun, exciting, original story. And I didn't know how he was going to top it with this sequel.

And now I get to say: I was pleasantly surprised by just how much I enjoyed Hollow City, especially given my expectations. It was as well written as Miss Peregrine, and the action was fun, intense, and often creepy, which is just what I like. The characters all stayed pretty true to who they were in the first book, which was great because I loved them all and knew them from the get-go.

If I had one critique, it's that the photos don't flow quite as nicely with the story as they did in the first book, but I think it's because of how they all came together. For Miss Peregrine, the photos came first, and essentially wrote the story, but for Hollow City, the story came first. My understanding is that Riggs then had to find photos that worked with the plot points, and while it was mostly still good, I don't think it was quite as seamless this way. But still, they were fun and eerie and lent a pleasant chill-factor to the book overall, especially when I got to a photo of the ONE THING that scares me more than just about anything...but I'll leave it up to you to guess as to which photo it actually was.

The ending is very exciting, and full of dreadful things. I won't give you any spoilers, but you do have to read through to the end. I'm already anxious for the third book in the series, but Riggs tweeted just yesterday that it won't be out for a couple of years. So until then, I'll perhaps go back and re-read the first, and flip through the photos anytime I need a jolt of fun in my day. Because that's what these books are to me: a great big jolt of fun.

Bookshots review written for LitReactor.com by Leah Rhyne

2

2

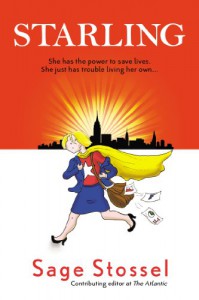

Bookshots: Bridget Jones with a cape

Title:

Starling

Who wrote it?

Sage Stossel, a cartoonist and contributing editor with The Atlantic

Plot in a box:

When her brother gets mixed up in a drug ring and the kingpin wants him dead, Amy Sturgess turns to her burnt-out superhero alter-ego Starling to save the day...and if she finds herself a boyfriend as she goes...well...no one ever said she couldn't have a little fun, too.

Invent a new title for this book:

Superpowers and Xanax

Read this if you liked:

Classic superhero comics with a twist, like The Incredibles. And if you like the idea of Wonderwoman, but without all the tits and ass, this book is for you.

Meet the book's lead:

Amy Sturgess is a lonely twenty-something marketing exec with a secret double-life: she's also a superhero called Starling, working as a vigilante on a volunteer basis. When the two lives don't exactly mix (in order to explain her many, sudden disappearances, she tells her coworkers she suffers frequent bouts of explosive diarrhea, and if that's not enough, one of her coworkers is out to steal her job), she turns to Xanax and therapy just to be able to sleep at night. Which would work...if only her superhero pager would stop going off all the time.

Said lead would be portrayed in a movie by:

I think Jennifer Lawrence has the perfect mix of awkward fumbling and beautiful confidence to pull off Amy Sturgess.

Setting: Would you want to live here?

A nondescript "big city" with a penchant for bank heists and art museum drama? Sure. Count me in.

What was your favorite sentence?

It's hard to find a favorite sentence in a graphic novel. It's not exactly written in a way that flows and lends itself to amazing sentences. But my favorite scene involved a wedding, Starling in a bridesmaid gown and hat (oh, the hat!!), and a wedding cake that's about to go DOWN.

The Verdict:

Sage Stossel is an acclaimed artist, illustrator, and writer, and Starling is proof she deserves the praise. A quick read (it took me less than a day to fly through this book), it was utterly engaging and entertaining.

As a heroine, Amy Sturgess is a classic superhero archetype (burnt out, exhausted, unappreciated, but unable to stop saving the world) turned slightly on her head. Think Wonderwoman, without the golden lasso and the revealing costume. In fact, in a particularly brilliant scene, Amy works with a team to choose her superhero costume, and after vetoing a few low-cut, high-legged options, she asks, "Who's designing these? A thirteen year old boy?" Sure enough...it is.

Amy is lonely and sad and boyfriendless, and her job is on the line since she often disappears mid-day to go save the world. Too bad no one at work knows that's what she's doing. They just think she has Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and it doesn't get much more embarrassing than that, does it? She's a great foil to the typical superhero, and somehow the fact that she has a bit of a Xanax addiction only makes her more endearing.

The writing is tight and the art is simple but enjoyable. The action is swift and, often, very funny. And as Amy works to save her brother from an evil drug kingpin, falling in love with a retired UFC fighter in the process, the chain-reaction is nerve-wracking and hilarious.

Overall, this is an entertaining book, and I enjoyed it tremendously. While it could easily get lost in the shuffle of the myriad graphic novels on the shelves of most bookstores, Starling definitely deserves a second (and third and fourth and fifth) look. Kudos to Sage Stossel for a fantastic book.

Review for Bookshots by Leah Rhyne

1

1